2 Preliminaries

2.1 Simple harmonic motion - a lightning refresher

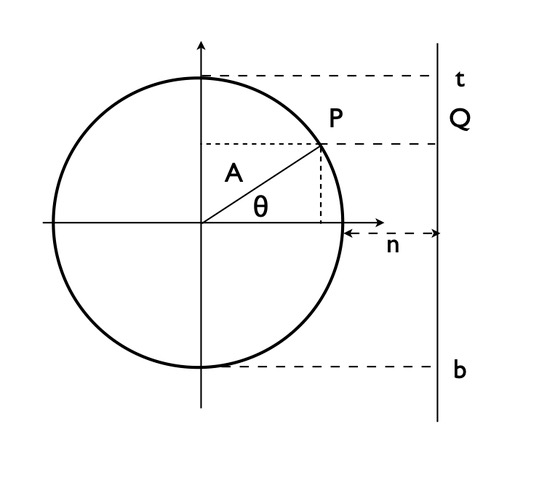

Let \(P\) be a particle moving at constant speed around a circle of radius \(A\), and \(Q\) be a particle moving up and down the segment \(tb\) in such a way that the \(y\)-coordinate of \(P\) and \(Q\) are equal at all times.

The points \(P\) and \(Q\) have coordinates

\[P=(A\cos\,\omega t, A\sin\,\omega t),\quad Q=(A+n,A\sin\,\omega t),\] where \(\omega\) is the angular velocity of the particle \(P\), with \(\omega t=\theta\). The positive real number \(n\) is not essential for our purpose.

Simple harmonic motion: an object that moves in such a way that its displacement from equilibrium can be written as \(A\sin \,\omega t\) (or \(A\cos\,\omega t\), or \(A\sin (\omega t+\varphi)\)) is said to execute a simple harmonic motion. In our setup, the particle \(Q\) executes a simple harmonic motion.

Amplitude of vibration: Maximum displacement (of the object executing the simple harmonic motion) from its equilibrium position. In the situation corresponding to Fig. 1, the amplitude is \(A\).

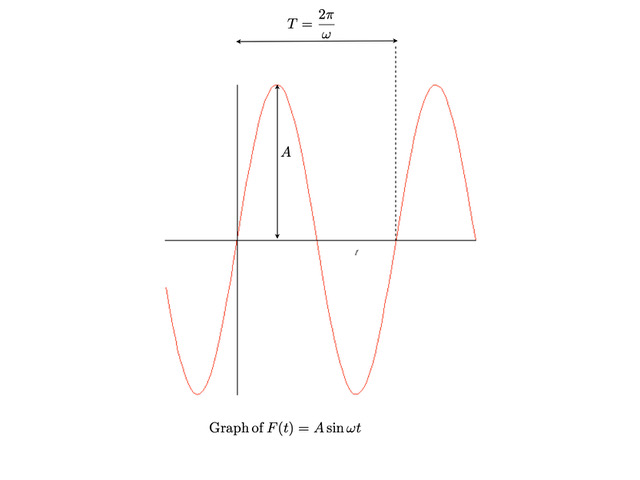

Period of simple harmonic motion: time needed to complete one oscillation (for the particle \(P\) to revolve once around the circle, i.e. time \(T\) such that \(\theta\equiv 2\pi=\omega T\). In mathematical terms, the period of the function \(F(t)=A\sin \omega t\) is the smallest positive real number \(T\) such that \(F(t+T)=F(t)\). It is indeed \(T=\frac{2\pi}{\omega}\) as

\[A\sin(\omega[t +\frac{2\pi}{\omega}])=A\sin (\omega t +2\pi)=A\sin \omega t.\] Frequency of simple harmonic motion: the inverse of the period \(T\), i.e. \(f=\frac{1}{T}=\frac{\omega}{2\pi}\).

All these concepts are illustrated in Fig. 2, which graphs the function \(A\sin \omega t\) as a function of \(t\). (Note that by choosing the origin of time appropriately, the graph also describes the functions \(A\cos\,\omega t\) and \(A\sin (\omega t+\varphi)\)).

2.2 Orthogonal functions

Consider two real-valued functions of a real variable, \(f_1\) and \(f_2\), defined on the interval \([a,b]\). Introduce the inner product of \(f_1\) and \(f_2\) on \([a,b]\) as, \[(f_1,f_2) \equiv \int_a^b f_1(x)\,f_2(x)\,dx.\]

Take \(f_1(x)=x,\,f_2(x)=x^2,\,[a,b]=[0,1]\), then \[(f_1,f_2)=\int_0^1\,x^3 \,dx = \frac{1}{4}[x^4]_0^1=\frac{1}{4}.\]

Take \(f_1(x)=x^2,\,f_2(x)=x^3,\,[a,b]=[-1,1]\), then \[(f_1,f_2)=\int_{-1}^1\, x^5 \,dx = \frac{1}{6}[x^6]_{-1}^1=0.\]

In the last example, \((f_1,f_2)=0\) on \([-1,1]\) and one says that \(f_1\) and \(f_2\) are orthogonal on \([-1,1]\).

More generally, the set \[\begin{equation} \label{ortho} \{\,\cos \frac{\pi k}{p}x\,\}_{k \in \mathbb{N}}\,\cup\,\{\,\sin \frac{\pi k}{p}x\,\}_{k \in \mathbb{N}} \end{equation}\] is an orthogonal set on \((-p,p)\), that is, given non-zero integer numbers \(m\) and \(n\), \[\begin{align} &\int_{-p}^p\cos \frac{m\pi}{p}x\,\cos \frac{n\pi}{p}x\,dx= \left \{ \begin{array}{l} 0\qquad {\rm for}\,\,m,n > 0, m \neq n\\ p \qquad {\rm for}\,\,m=n,\end{array} \right. \label{coscos}\\ &\int_{-p}^p\sin \frac{m\pi}{p}x\,\sin \frac{n\pi}{p}x\,dx= \left \{ \begin{array}{l} 0\qquad {\rm for}\,\,m,n > 0, m \neq n\\ p \qquad {\rm for}\,\,m=n,\end{array} \right. \label{sinsin}\end{align}\] while \[\begin{equation} \int_{-p}^p \sin \frac{m\pi}{p}x\,\cos \frac{n\pi}{p}x\,dx=0 \label{sincos} \end{equation}\] for \(m,n > 0, m \neq n\) as well as for \(m=n\). Moreover, \[\begin{align} &\int_{-p}^p 1 \cdot \cos \frac{m\pi}{p}x\,dx=0\qquad {\rm for}\,\,m> 0, \label{1cos}\\ &\int_{-p}^p 1 \cdot \sin \frac{m\pi}{p}x\,dx=0\qquad {\rm for}\,\,m> 0.\label{1sin}\end{align}\] These results are proven by explicit integration, using the well-known trigonometric identities \[\begin{aligned} \sin(a\pm b)&=\sin a \cos b \pm \sin b \cos a,\\ \cos(a\pm b)&=\cos a \cos b \mp \sin a \sin b.\end{aligned}\]

For \(p=\pi\), one obtains the following important relations

\[\begin{aligned} &&\frac{1}{2\pi} \int_{-\pi}^{\pi} \sin mx\,\cos nx \,dx =0\qquad {\rm for} \,\,m,n \in \mathbb{Z},\\ &&\frac{1}{2\pi} \int_{-\pi}^{\pi} \sin mx\,\sin nx \,dx=\left \{ \begin{array}{l} 0\,\,{\rm if }\,\,m \neq n,\\ \frac{1}{2}\,\,{\rm if }\,\,m =n\neq 0,\\ 0 \,\,{\rm if }\,\,m =n=0, \end{array} \right.\\ &&\frac{1}{2\pi} \int_{-\pi}^{\pi} \cos mx\,\cos nx \,dx=\left \{ \begin{array}{l} 0\,\,{\rm if }\,\,m \neq n,\\ \frac{1}{2}\,\,{\rm if }\,\,m =n\neq 0,\\ 1 \,\,{\rm if }\,\,m =n=0. \end{array} \right.\end{aligned}\]

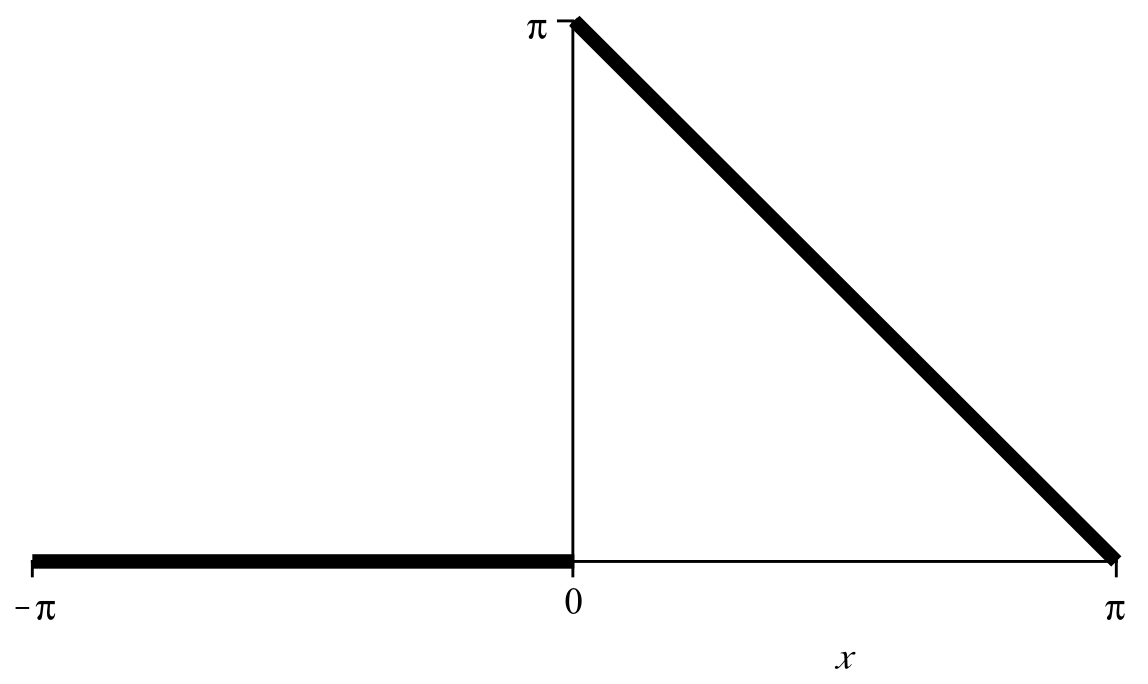

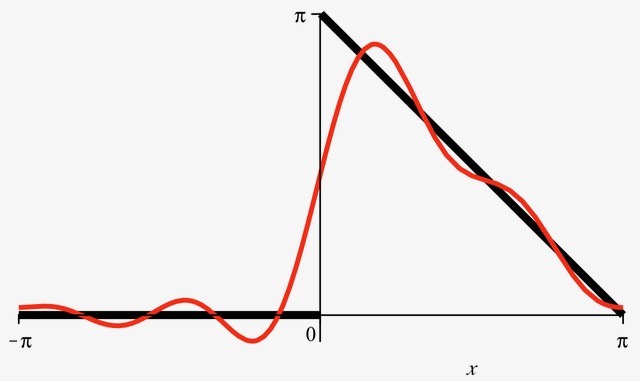

![fig: A piecewise continuous function on [-\pi,\pi] (left) generates a Fourier series converging to the function on the right.](Figs/cgence1.jpg)

![fig: A piecewise continuous function on [-\pi,\pi] (left) generates a Fourier series converging to the function on the right.](Figs/cgence2.jpg)